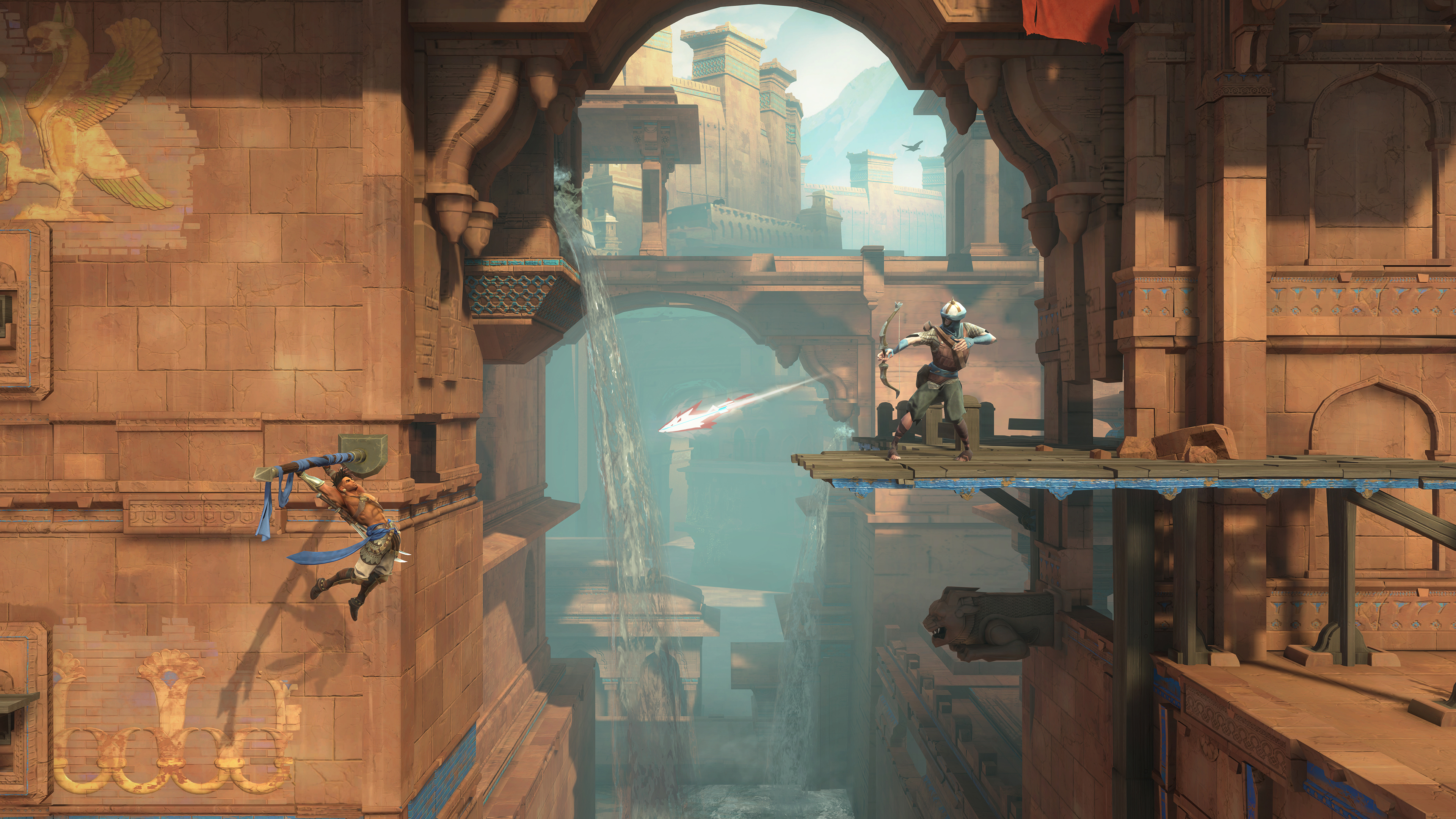

Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown is designed to be hard. It’s also designed, from the ground up, to be accessible. These things aren’t at odds with each other. Ubisoft Montpellier integrated accessibility options into every part of the game from the start; there was no one team designated to do the work, senior game designers Christophe Pic and Rémi Boutin told Polygon ahead of Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown’s Innovation in Accessibility win at The Game Awards 2024. Up against Call of Duty: Black Ops 6, Diablo 4, Dragon Age: The Veilguard, and fellow Ubisoft game Star Wars Outlaws, the Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown team set a new standard for accessibility in the brutal Metroidvania genre — and was rewarded for it.

“Some developers can fear that accessibility can dilute your game’s strengths, and I think it’s the opposite with all our accessibility features,” Boutin told Polygon in a sit-down interview ahead of the show. “We allow more players to enjoy exploration, more players to enjoy the combat. And at the end, when we read reviews, the game was still considered very, very challenging.” It’s the nature of the game and its controls that allows for this feeling; what’s unique about it is the sense of freedom and fluidity of its movement. “Our controls bring immediate fun, and make the game easy to learn, but hard to master,” senior producer Abdelhak Elguess said.

Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown was released in January and was an immediate hit with critics, and it was the first big Prince of Persia game since 2010’s Prince of Persia: The Forgotten Sands. There was a lot of pressure to get the game right. “We started first with the DNA, because when you attack such a big brand, you have to respect the brand, but we also wanted to surprise our players,” Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown game director Mounir Radi told Polygon.

Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown indeed has a lot of features that players have come to expect from games, like multiple difficulty options, subtitles, and aim assist. But where Ubisoft’s Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown’s accessibility shines the brightest is in how its development process — accessibility built into each step — allowed its developers to innovate. Boutin pointed to this process as the explicit reason for some options, like the high-contrast switch. A first for Ubisoft, the high-contrast mode impacts colors and contrast. One developer noticed that during cinematics, the mode spoiled certain story details, like an enemy becoming an ally, for instance. (All pieces of data in Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown are labeled internally so that a mode like this could be applied correctly to different assets.) The developer then added an option to turn off the switch for cinematics so that players could prevent themselves from being spoiled. “This is the kind of detail that comes with the fact that everyone was involved in accessibility,” Boutin said.

The big thrill of a Metroidvania game like Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown is exploration. The team wanted players to feel lost, but not too lost. And so the team developed the guided mode to help with that. “It was a bit tricky because we want the player to be lost,” Pic said. “It’s important because it’s exploration-driven. We want the player to explore by himself to discover everything — the treasure, the shortcuts. We developed the guided mode to help players that are not used to using the map all the time like you do when you play a Metroidvania game.” The primary objectives are on the map, but the route to get there is still down to exploration.

Image: Ubisoft Montpellier/Ubisoft

“We kept the essence of the thrill of exploration,” Boutin added. “We know that some players drop some games because they hate being lost, but they miss the feeling of exploration. That’s what motivated the creation of the screenshot marker.”

The screenshot markers in Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown are called memory shards, which allow players to take screenshots and pin them to the map — it’s like scribbling something down in a journal, but right on the screen. Boutin had been thinking about how a photo mode could be used in gameplay already, and when the Ubisoft team implemented its prototypes, it simply worked, albeit with some limitations. (Boutin added that the screenshot feature was originally more complicated, and it took some time and iteration to strip it down to its final version.) “It was a good way to keep the player active in the observation of the world,” Pic said.

During the development process, Boutin and Pic said, the biggest lesson was the importance of distributing accessibility throughout the game by default — as part of the original design process, with all developers involved. At first, there was some reticence among the team about this, but everyone was on board when they saw how the process worked; everyone had input. To be nominated for this award among other games with innovative design (Boutin specifically called out Diablo 4’s on-screen descriptors) — and then to win — is a reminder that the process works.

Though the Ubisoft team that worked on Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown has been disbanded, moving on to projects like Ghost Recon, Rayman, and Beyond Good and Evil 2, the team members are immensely proud of the work they created. Radi confirmed to Polygon that Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown sold more than 1 million copies, but an Insider Gaming report from October suggested that the game didn’t meet Ubisoft’s internal expectations.

“Honestly, we had a tough year with Ubisoft,” Radi said. “Each month is a new problem. But with these nominations, it’s our way to show what kind of game we can achieve when we work together and when we work with our heart.”