In 2024, you can’t throw a stone without hitting an anime fan — not literally, of course. But what once felt like an exclusive club has become a mainstream, global phenomenon, appearing on everything from major streaming services to giant movie screens. And millions of today’s anime fans have the same place to thank for their introduction to the medium: Toonami, Cartoon Network’s beloved late-’90s/early-aughts after-school programming block.

Considering its popularity, it makes sense that the lineup, which now airs on Adult Swim, began producing original anime of its own. But as an American-owned and -operated sub-brand, Toonami’s original anime are special: They’re not only high-quality, they’re authentic, too. After nearly 30 years on the air, and a dozen exclusive anime produced by major studios, Toonami remains one of the lone non-Japanese brands regularly creating genuine Japanese shows. In that time, it’s nailed down a formula that no one else has managed to replicate: one of authenticity, self-promotion, and capturing the zeitgeist.

Launching in 1997, Toonami’s programming was a unique bedrock for Cartoon Network in the late ’90s and early aughts. While other American channels aired popular anime — like Kids’ WB and Fox Kids, homes to Pokémon, Yu-Gi-Oh, Digimon, the infamous 4Kids dub of One Piece, and more — Cartoon Network’s Toonami had the most robust collection of series. Every afternoon, kids could come home and watch everything from classics like Dragon Ball and Sailor Moon to fan favorites like the Gundam franchise and Outlaw Star. (The channel’s Toonami block also boasted shows like Hamtaro, which was maybe too cutesy for action anime-lovers, but iconic to this writer.) As broadcast networks and English-dubbed home videos made these shows more accessible to mainstream audiences — not to mention the Pokémon craze — anime’s stateside popularity grew. With its diverse programming, Toonami developed an identity as a purveyor of high-quality goods.

But it’s one thing to showcase great shows, which Cartoon Network did both during Toonami’s daytime hours and weekend slot as part of Adult Swim (how many Western audiences were first traumatized by Neon Genesis Evangelion). It’s another to make them, which the network did for the first time in 2003 — and continued to do for the next 20-plus years.

The Big O aired on Toonami in 2001, quickly gaining acclaim for its spin on the popular mecha genre. Stylistically, it was a mashup of Japanese and Western artistic and storytelling sensibilities: The main character was named Roger Smith, a peak American name. Smith is embroiled in a noir-inspired mystery involving the destruction of both the world and its survivors’ memories, calling upon a giant robot when necessary.

Produced by acclaimed studio Sunrise, which also helmed Toonami/Adult Swim smash Cowboy Bebop and the Gundam franchise, The Big O became an early success story for the block. But the series only ran for one season and 13 episodes — akin to a show like Bebop, but unlike the big hits that it felt primed to be. Not only that, but The Big O ended on a cliffhanger, an intentional move to bait a studio into ordering a season 2.

In January 2003, Cartoon Network took Sunrise up on it, teaming up to create a second season of The Big O: The Big O II, which aired exclusively on Adult Swim in the States. By hooking back up with the original studio and creative team, the American network aimed to recapture and honor The Big O’s spirit. It reportedly had little intervention in the production, other than funding and offering two notes on its story. (One of them: Solve the mystery.) And while its ratings weren’t enough to warrant a season 3, it established Cartoon Network’s anime bona fides in spectacular fashion: Here was a company unafraid to not just license kid-friendly, toy-ready series, but also willing to spend money on satisfying audiences by keeping those shows going.

Only two years later, the company proved that The Big O II project wasn’t a one-off. Cartoon Network (and Williams Street, the subsidiary that runs Adult Swim) teamed up with Production I.G, a storied studio that had worked on everything from Ghost in the Shell to Kill Bill, to turn a series of five animated shorts into an exclusive anime for Toonami. In a press release, Production I.G touted IGPX: Immortal Grand Prix as “the first instance of a U.S.A. cable network working directly with a Japanese animation studio to create an original series.” (The announcement also refers to Cartoon Network as “the biggest animation channel in the world.” Oh, how the mighty have fallen.) Toonami rigorously publicized the show, asserting how big of a deal it was: It had capitalized upon a near decade of dominance as TV’s most diverse anime block, especially with its crossover hits in the mecha subgenre, to authentically enter the field.

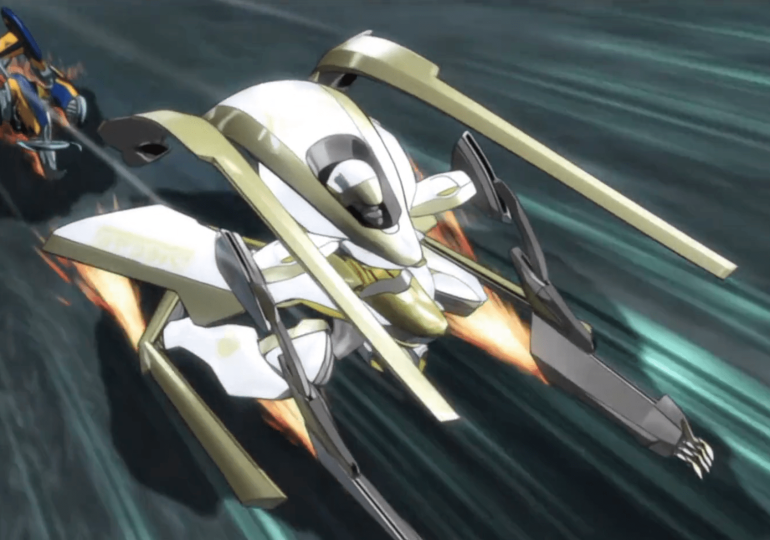

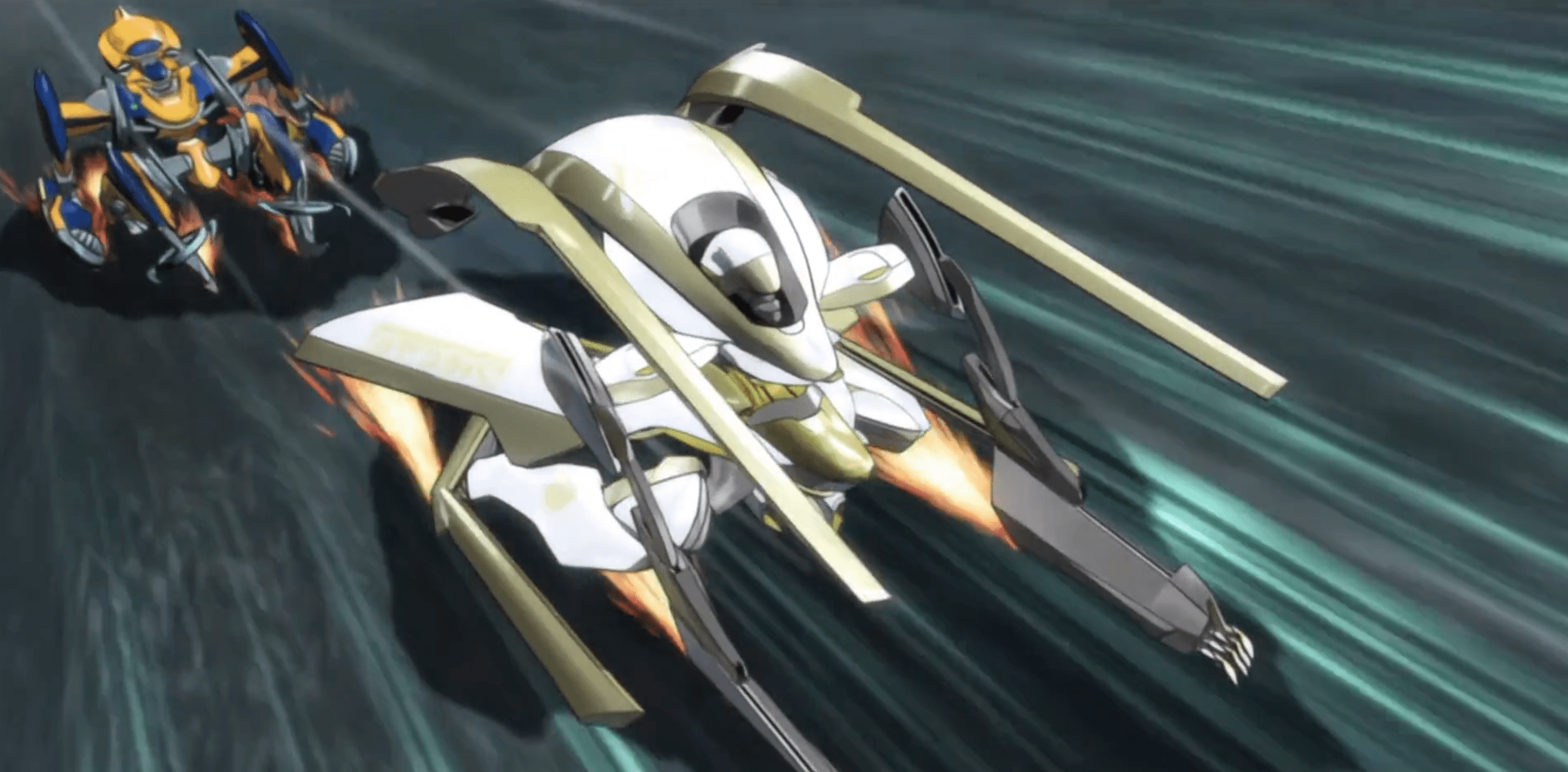

Image: Production I.G, Cartoon Network/Discotek Media

As far as mecha anime go, IGPX is mostly novel for being a Toonami original series exclusive to the block, which was unprecedented for its time. It blended 2D and CGI animation for its futuristic story about a sport where giant, human-piloted mechs race each other. If you came for the mechs, you wouldn’t leave displeased, but this was more of a racing drama than a Gundam-style giant-robot show. Viewers were cold on the series upon its initial airing, Toonami co-creator Jason DeMarco noted in a later interview: “On message boards after the [episodes] aired, it seemed like we were always getting ripped a new one,” he said, due to its less-straightforward approach to the genre. Still, it managed to run for 26 episodes over two seasons, with DeMarco and co-creator Sean Akins publicly stating their intentions for IGPX to kick off a long line of Toonami’s anime co-productions.

IGPX marked a turning point for Toonami, but not in the way that DeMarco and Akins hoped. In 2008, two years after IGPX’s final episode aired, the block went off the air. Despite the continued popularity of shows like Naruto and One Piece (even with that infernal 4Kids dub), anime’s stateside popularity was no longer at its Dragon Ball Z-era height. The once-booming home video market, which was a huge part of anime’s global success, was on the decline — in part because of the little thing called the Great Recession going on at the time, though some discouraged anime fans argued that the medium itself was also in a creative rut. Toonami saw falling ratings, and after a switch from weekdays to Saturday night and a dwindling amount of new programming, Cartoon Network sunsetted it entirely. DeMarco would later say in an interview that Toonami’s cancellation was likely due to, among other things, “a cross between the wider cultural consciousness moving away from anime and our network having different priorities.” After a decade of trendsetting content, Toonami went out with a whimper.

Toonami took a four-year break from the air, until it returned as part of Adult Swim in 2012. The block was met with much fanfare, as it committed to recapturing a mature audience — no more kiddy shows like Yu-Gi-Oh GX and Bakugan Battle Brawlers. Old favorites like Cowboy Bebop returned to air, alongside newer hits like Bleach and Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood. Adult Swim’s Toonami redux was curated in a way that appealed to nostalgic viewers who grew up with the block and those dipping their toe into the anime waters. And this only became more aggressive when the network once again dove into original anime production.

First, the new Toonami had a coup of a premiere to tempt old-school viewers: 2014’s Space Dandy, the new anime from the creator of Cowboy Bebop. It locked down the world-exclusive premiere of the show, capitalizing on the continued love and acclaim for Bebop to bolster the block’s image. And it surrounded Space Dandy with other massive hits: Gurren Lagann, Attack on Titan, and Dragon Ball Z Kai, a filler-free recut of the original series. Toonami had reasserted itself as an anime hotspot by giving its original fans the chance to rewatch shows like Dragon Ball Z, like the good old days, while introducing them to the action anime’s heir apparents, from Soul Eater to One-Punch Man. Just as Toonami helped anime fans stay hip in the aughts by showing the best-known series, its Adult Swim revival helped viewers stay on top of the internationally renowned Dragon Ball Zs of today — a crash course in anime coolness.

Nostalgia seemed to be a guiding force for Adult Swim’s version of Toonami, both on a programming level and a production one. The most overt indicator that the network’s new MO was tantalizing viewers with the promise of the past was the network’s biggest commitment to exclusive anime yet: the return of FLCL, co-produced by Adult Swim.

Produced by Evangelion studio Gainax, FLCL aired on Adult Swim’s late-night anime block in 2003. It garnered a cult audience for its frantic pacing, absurd characters, and wholly original storytelling; it’s a show that promotes marathon-viewing, the kind that repertory theaters will screen at midnight to a not-so-sober crowd. FLCL’s six episodes became legendary, and it reran often upon Toonami’s return in the 2010s. Yet it was still something of a shock when, in 2016, Adult Swim announced it was co-producing two new seasons of the series to air on Toonami.

FLCL Progressive and FLCL Alternative (each named after a rock subgenre, befitting the series’ punk ethos) aired between June and October 2018, a punchy, 12-episode run that deviated from the original series. Frequent partner Production I.G, which also worked on the original series, returned; so did the Pillows, the J-rock band behind season 1’s iconic theme and soundtrack. And the pink-haired, guitar-playing agent of chaos Haruko returned as the show’s lead. Other than that, the new FLCL was its own beast, expanding upon whatever there was of the original series’ lore. The action was still zany, but the endearingly frantic animation was more muted. Ultimately, none of the seasons — including two more in 2023, the prequel FLCL: Grunge and sequel FLCL: Shoegaze, in which Haruko was absent — received the same level of fanaticism and praise as Gainax’s original.

Even if they’re usually not as good as they hoped for, fans clamor for reboots of beloved, short-lived series like FLCL. Adult Swim doubled down on its renewed commitment to anime by bringing one of its hit acquisitions back in a way that was mostly authentic, even if it was imperfect. But “mostly” is crucial for a show as stylistically singular as this one. The company’s ability to resurrect the series — for four additional seasons, no less — was limited by the available staff to work on it, which mostly did not include the series’ original creators, like director Kazuya Tsurumaki or screenwriter Yōji Enokido. The first season’s absurd scrappiness was a huge part of the charm — something that a highly touted reboot could not replicate. Adult Swim successfully threw its weight around here, but the muted reception underscored that the mere act of throwing money behind a beloved anime property may not always be enough.

Where to find the Toonami anime canon

Where you can find the Toonami originals you’ve read about here: Shows like The Big O are a little tough to watch outside of YouTube bootlegs. But not all of them are hard to track down:

- IGPX – Adult Swim’s website and Sling with ads

- Space Dandy – Crunchyroll and Hulu

- Shenmue, Fena: Pirate Princess, and Blade Runner: Black Lotus – Crunchyroll

- FLCL: the original on Hulu, Alternative and Progressive on Crunchyroll, and Grunge and Shoegaze on Max and Hulu

- Ninja Kamui, Rick and Morty: The Anime, and (eventually) Uzuamki can be found on Max

The anime Toonami helped popularize: At least to start with…

- Crunchyroll: Case Closed, Code Geass, Cowboy Bebop, Dragon Ball, Dragon Ball Z, Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood, Mobile Suit Gundam, Naruto, Trigun, YuYu Hakusho

- Hulu: Bleach, Rurouni Kenshin

- Netflix: Death Note, Neon Genesis Evangelion, One Piece

Still, the effort pushed open a door to way more originally produced anime than ever before. In 2018, Adult Swim announced that it had hooked up with Western anime power-player Crunchyroll to bring three series to the network. The streaming service had amassed a dedicated viewer base since its 2006 launch, thanks to its huge library of dubbed and subbed anime; at the time, it boasted 1 million subscribers and was growing quickly. (Today, it has 15 million.) Released in 2021 and 2022, two were once again based on existing properties popular with the typical adult Toonami viewer: Blade Runner: Black Lotus and, slightly more surprisingly, Shenmue. (The other, Fena: Pirate Princess, was an original seafaring fantasy.) This partnership ended fairly abruptly after Warner Bros.-owned Crunchyroll was acquired by Sony, a competitor. But considering Toonami once took a low-ratings-induced hiatus, healthy competition is a good thing: Major companies see a reason to spend big bucks on anime again.

In 2024, Adult Swim returned undeterred and with plans for three more original anime. First came February’s Ninja Kamui, an action-heavy series co-produced by newer studios E&H Production and Sola Entertainment. But it’s this fall’s two entries into the Adult Swim/Toonami anime canon that are most intriguing: a Rick and Morty anime, a surreal take based on the sci-fi comedy, and an adaptation of horror masterpiece Uzumaki. Both suggest an interesting path forward for the network as it carves out its anime-powered future, one that is self-referential and experimental.

Rick and Morty: The Anime is a full-length take on popular shorts commissioned by the network in 2020 and 2021. Like those shorts, the endeavor gives professional anime director and self-proclaimed superfan Takashi Sano the chance to play with the show’s world and the medium. It also fills the Rick and Morty-sized gap in Adult Swim’s fall schedule, with season 8 still in production. That dual purpose works in Adult Swim’s favor, even if the show itself hasn’t quite gelled with fans. Based on the show thus far, it seems the network is willing to be flexible with its own properties, and not only that, but that it will get weird with them.

Uzumaki, meanwhile, appears to be what all of this work has been leading up to all along. The long-awaited adaptation of Junji Ito’s acclaimed manga was first announced in 2019 for a 2020 launch. Then the COVID-19 pandemic happened, and repeated delays ensued. The show is finally due out in September of this year, barring any last-minute changes. But the prolonged wait for the adaptation, pacified with stellar teasers that highlighted how dedicated the network and animation studio Drive were to getting it right, exploded the hype. What was most compelling about Uzumaki’s teasers was how closely they paid attention to detail, recapturing Ito’s art style to a T. Unfolding in black and white, it even uses the manga as a storyboard, with many shots taken directly from the mangaka’s work. Between the impressive animation and the popularity of the Uzumaki manga, this is a major coup for Adult Swim’s Toonami lineup — it need only stick the landing for this four-episode miniseries in order to strike gold with fans.

It’s not just a big deal that a seeming labor of love like Uzumaki exists at all. It’s also a big deal that Toonami is where it will air — because Toonami is no longer the biggest, let alone only, game in town. Twenty-one years after The Big O II, Adult Swim’s Toonami block is now one of several Western programmers investing in the Japanese anime game. But while Netflix and Crunchyroll have followed in its footsteps, it’s important to note just that: Toonami led the charge. That it continues to chase these projects, and interesting ones at that, is a testament to decades of fannish passion for the medium — not just chasing trends. And after decades building toward producing a big-deal show like Uzumaki, Toonami has more than earned the bragging rights that come with it.